Nine years ago, Rosalie Tallbull, 77, received a call from the child welfare system to pick up her grandson, 4-year-old Mauricio, right away or he would go into foster care with people he didn’t know. He had been removed from her daughter’s home in Denver, Colorado due to a domestic violence incident. Her daughter had long-standing problems with alcoholism. Rosalie and her granddaughter, Amber, age 39, also lived in Denver and they both had cared for Mauricio on and off all his life. Rosalie was more than willing to take Mauricio, but that day was the beginning of years of a confusing and sometimes baffling journey with the child welfare system, as well as many court appearances.

In the Midst of Trauma, Rosalie Tries to Keep the Family Together

When she got the call, Rosalie, a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe, was in Montana on the reservation, caring for her mother who was in hospice care. “I knew once he got into the foster care system with strangers it could be a long time and maybe impossible to get him back to our family,” explains Rosalie. She arranged for her granddaughter, Amber, to leave work and pick up Mauricio immediately and keep him until she could get a flight home.

Two days later she was awarded temporary physical custody in a court hearing. Rosalie had no experience with the child welfare or court systems and was confused by the proceeding.

“I was given absolutely no information. I really didn’t know what was happening or what I needed to do. I didn’t know what temporary custody meant. I didn’t even know what had happened with my daughter and I couldn’t reach her.”

- Rosalie Tallbull

A caseworker from the county child welfare office told her she needed to be at her office at 10:00 am the next morning. She would not tell her anything more about why, what to expect or even what her last name was. “That was it, and she walked away,” says Rosalie.

“Mauricio was very, very traumatized that first night that Amber had him,” shares Rosalie. “She had to call a friend to sit up with her because they had to hold him all night long because he would have nightmares and screaming. The same thing happened that next night after I returned. It was very traumatizing for all of us. And then the very next day, I had to take him to this department not knowing why or what was going on.”

Without a car at the time, she took three buses with Mauricio to get to the office the next morning.” When she arrived, the caseworker took Mauricio out of the room. “I asked where she was taking him, and she wouldn’t say.” Rosalie eventually asked the receptionist who explained that Mauricio was having supervised visits with his parents. Over the coming months, the caseworker treated her very poorly, repeatedly leaving her in the dark. And Mauricio did not receive the services and supports he needed and should have received.

Rosalie attempted to contact her Northern Cheyenne Tribal Indian Child Welfare (ICWA) office for assistance. But she was told that they just didn’t have enough funding to help tribal members who were out of state.

It was two weeks before Rosalie had a meeting where she learned a bit more about what was happening and what to expect. She learned that Mauricio was in the legal custody of the child welfare department and that she just had temporary physical custody. “I didn’t know what that meant. I asked what my rights were and what their role was,” says Rosalie. She was never told she could become a kinship foster parent. She requested mental health support for her grandson but got no response.

Challenges Continue for Rosalie, Attempting to Navigate Inequitable Systems

For months, she wasn’t given clear information or any services or supports for Mauricio. She did not understand why her caseworker wouldn’t help.

“There was no communication barrier, I speak perfect English. But I was given no courtesy, no information and it was a very trying time.”

- Rosalie Tallbull

Rosalie, who was retired, struggled to financially provide for Mauricio, “I had very little, just what I had in my savings account,” she shares. When she received temporary custody, Mauricio only had the clothes he was wearing. She had to purchase clothes and other items that he needed.

When she was at the child welfare office for a visitation meeting, she saw a woman go to the receptionist and request her check. She asked the woman what the check was for. Rosalie learned that it was emergency funds for the child in her care. Rosalie then asked her caseworker about getting emergency funds for Mauricio; her caseworker said she knew nothing about it and would ask. But Rosalie never got an answer. After several months, she asked for a meeting with her caseworker’s supervisor, but the situation continued unresolved. One of the main issues was that the child welfare case was in Arapahoe County and Rosalie resided in Denver County. Both counties insisted that the other county was responsible for handling the case.

Then one day, at the child welfare office, Rosalie noticed a flyer on the bulletin board about a grandparent support group. Seeing that notice turned out to be the key to finally accessing the supports that Mauricio needed. The support group moderator helped her understand the system. The group also had speakers who educated the grandparent caregivers.

Rosalie continued to advocate for Mauricio as best she could. Concerned about delays in his development due to neglect from her daughter, she asked about sending Mauricio to preschool. The caseworker accused her of just wanting a babysitter. “She said it to my face and I was so shocked. There were other parents in that reception area. I burst out crying and turned around and walked out of there.” The grandparent support group moderator told her about a Montessori preschool whose staff helped her successfully complete the paperwork for the county to pay for the preschool.

The grandparent support group helped Rosalie connect with a mental health agency where her grandson received treatment, but it took several months before the child welfare department began paying for the mental health care. About nine months after receiving temporary custody of Mauricio, thanks to help from the support group, Rosalie started receiving support from Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Several months later she was successful in getting Mauricio a Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) child-only grant for financial assistance. After about two years, Rosalie was given full legal custody of Mauricio.

“Now I can make parental decisions for him with school and health care and everything.”

- Rosalie Tallbull

His parents are ordered to pay child support but rarely do so. However, when child support is issued to the custodial grandparent it is considered additional monthly income and almost always reduces SNAP and TANF payments, or results ineligibility for any payments.

Rosalie Reflects After 9 Years

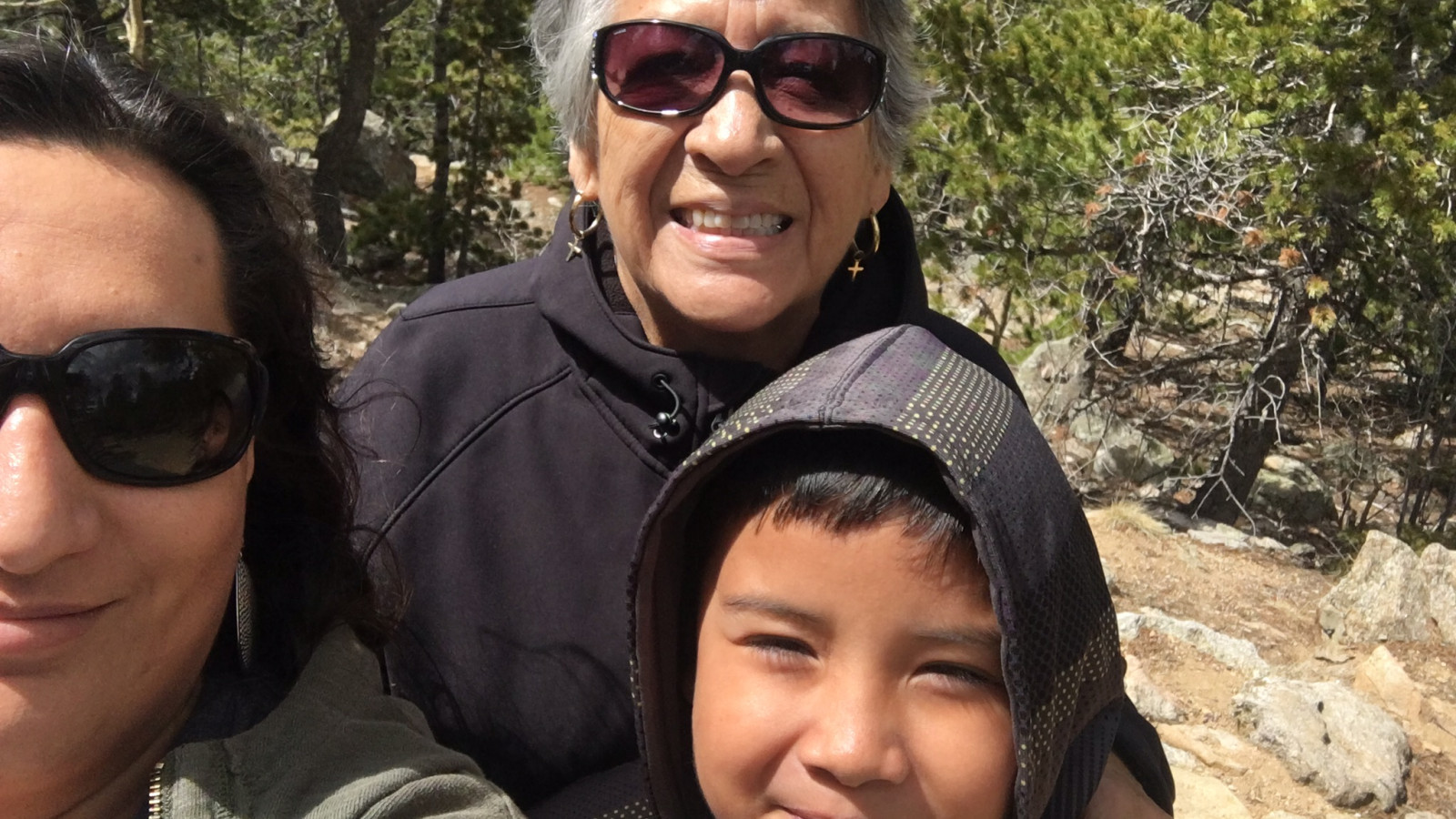

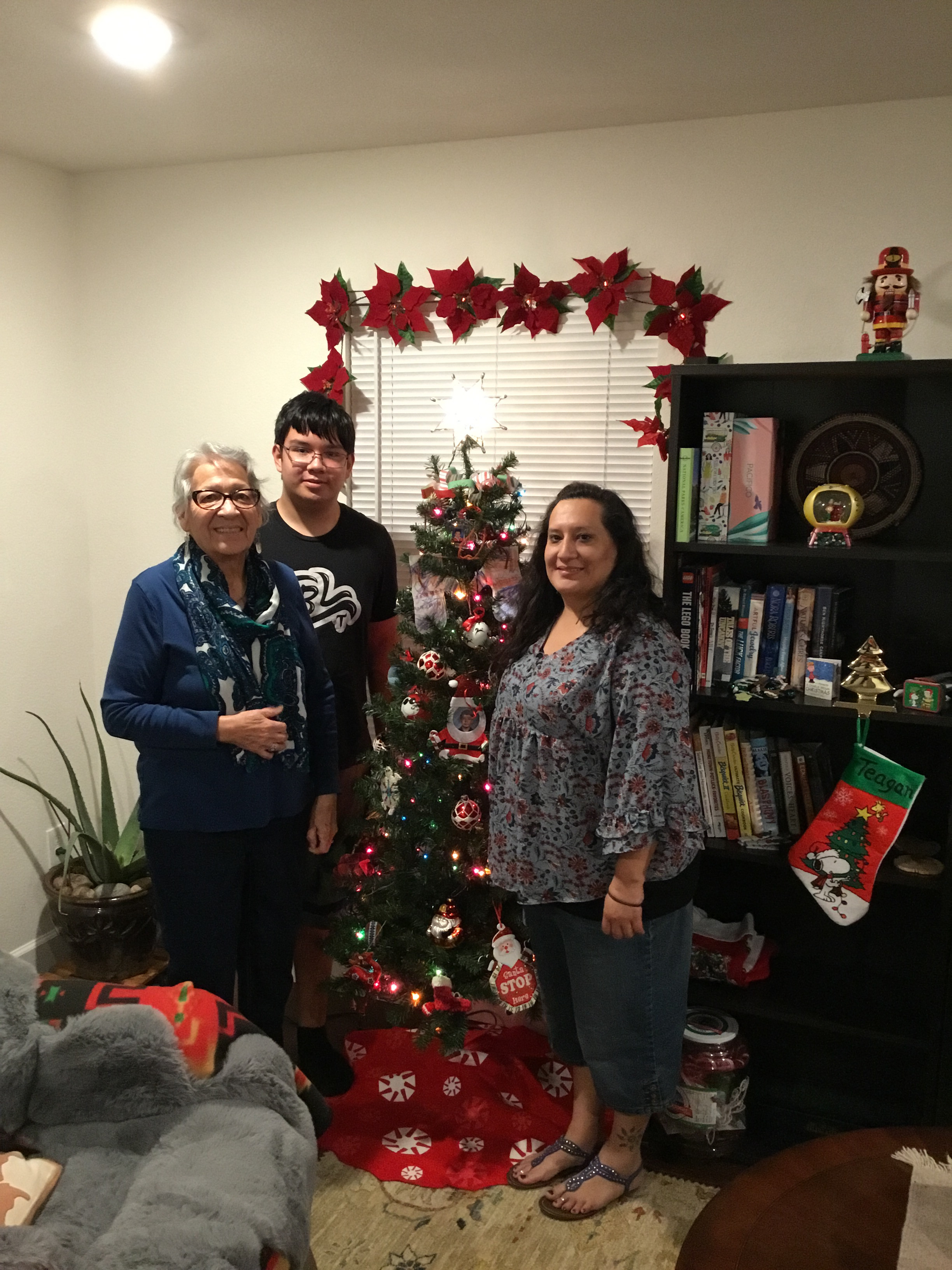

Mauricio is now thirteen and an eighth-grader; he is doing well.

“He’s a very handsome, responsible young man. We come from a real close family. He was so traumatized in the beginning, but because my family all banded together and took care of him that’s how he got better.”

- Rosalie Tallbull

Rosalie says she doesn’t know what she would have done without the grandparent support group, “The moderator was the one person who helped me the most.” As for her experience with the caseworker, Rosalie later learned that inexperience was likely a major factor, as it was her first assignment.

Rosalie is one of millions of grandfamily caregivers in the United States. To help other grandfamilies avoid the challenges she faced, Rosalie has become an advocate and active member of the grandparent support group. She also served in the Colorado Department of Health and Human Services Family Voice Council, which was created in 2019, and she currently serves as a member of Generations United’s GRAND Voices Network.

While grandfamilies are of all geographic locations, socio-economic levels, and races/ethnicities, Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native children are the most likely to be in grandfamilies. Grandfamilies arise out of events that separate children from their parents, such as death, including from COVID-19, substance use, incarceration, mental illness, divorce, or military deployment. The systems and services that help U.S. families—in areas such as housing, education, and health care—were not designed for grandfamilies.

Read more stories and learn how policymakers can help create policies and systems that better support grandfamilies in Generations United’s 2021 State of Grandfamilies report.

This story was re-posted with permission from Generations United.